A Guide to the Spirits and Deities of Tibet

In the rich tapestry of Tibetan spirituality, the landscape is not merely earth and sky, but a vibrant, living entity imbued with countless unseen forces. Among these, the various classes of spirits, or nyen (gnod sbyin), play a significant role, shaping both the physical and metaphysical worlds. These spirits, often misunderstood or oversimplified in their depiction, are complex beings, embodying both benevolent and malevolent aspects, reflecting the intricate relationship between humanity and the natural world.

PARANORMAL

Tsering

5/8/20249 min read

Having introduced the general concept of these spiritual entities, we now turn our attention to one of the most prominent and frequently encountered: the Tsen (btsan). The Tsen are a class of powerful, often formidable, spirits particularly associated with mountains, rocks, and the rugged, high-altitude terrain that defines much of Tibet. They are believed to dwell in peaks, cliffs, and sometimes even in specific trees or springs within their designated domains.

Visually, a Tsen is typically depicted as a fierce warrior, almost always red in color, a hue that symbolizes both their fiery temperament and their connection to wrathful deities. They possess one face and two hands, often grasping weapons such as swords or spears, indicative of their protective and sometimes aggressive nature. Their attire reinforces their martial identity: they wear helmets and armor, often adorned with intricate designs, signifying their status as powerful guardians of their territories. Perhaps most strikingly, they are invariably shown riding atop a horse, frequently also red, a powerful symbol of their swiftness and their untamed, wild essence. This image of the red warrior on a red horse is iconic and instantly recognizable within Tibetan art and folklore, embodying the raw power and indomitable spirit of the mountain itself.

However, the Tsen are not simply one-dimensional figures of aggression. Their nature is far more nuanced. While they can be fiercely protective of their domains and, if angered or disrespected, can inflict harm upon those who trespass or act inappropriately, they are also capable of being benevolent. When propitiated correctly and treated with reverence, Tsen can be powerful allies, bestowing blessings, protecting travelers, and even safeguarding the environment. They are seen as guardians of hidden treasures, both material and spiritual, and are often invoked in rituals to ensure the prosperity and well-being of a region.

The relationship between humans and Tsen is one of delicate balance. Tibetan tradition emphasizes the importance of respecting these indigenous spirits, understanding their territories, and making offerings to maintain harmony. Failure to do so can lead to illness, misfortune, or natural disasters, as the Tsen are believed to control aspects of the local environment. Conversely, a respectful and harmonious relationship can lead to mutual benefit, with the Tsen ensuring the bounty and safety of the land.

In essence, the Tsen are a profound embodiment of the Tibetan worldview, where the natural world is alive with consciousness, and every mountain, rock, and stream has its own guardian. They serve as a constant reminder of the power and majesty of nature, and the deep interconnectedness between human existence and the unseen forces that govern the very ground beneath our feet. We will now explore further specific types of Tsen and their particular characteristics.

NYEN

While the term nyen (gnod sbyin) can sometimes be used as a broader category encompassing various indigenous spirits, more specifically, the Nyen are a class of powerful earth spirits. Unlike the fiery, often red Tsen who are more associated with mountains and the upper reaches, the Nyen are closely tied to the ground, rocks, cliffs, and sometimes even trees and springs, often dwelling within the earth itself or in caves and subterranean realms.

They are typically depicted as malevolent or mischievous in nature if provoked, and are known to cause illness, particularly skin diseases, or other misfortunes when their domains are disturbed or disrespected. They are often associated with epidemics and plagues.

In terms of appearance, while less consistently portrayed than the Tsen, the Nyen are often imagined as fierce and intimidating figures, sometimes with a dark or earthy complexion. They can be quite territorial, and their presence is often felt in places that are considered sacred or dangerous.

Despite their potential for harm, like many Tibetan spirits, the Nyen are not inherently evil. They can be propitiated through rituals and offerings to avert their wrath and even to gain their benevolent assistance, particularly in matters related to the land and its resources. They are an integral part of the intricate web of nature spirits that Tibetans acknowledge and interact with, highlighting the profound respect and caution with which the natural environment is viewed.ere...

KLU

The Klu are serpentine spirits, primarily associated with water and the subterranean realm. They are often described as naga-like beings, drawing parallels with mythical serpents from Indian traditions, but with unique Tibetan characteristics.

Klu are the guardians of all bodies of water, including lakes, rivers, springs, wells, and even the vast oceans. They also reside in the moist earth beneath these waters, within subterranean caverns, and occasionally in specific trees that are closely connected to water sources. They are fundamentally seen as the "owners" of water.

The most common depiction of a Klu features a human upper body joined with a serpent's tail for the lower half. Their skin color often reflects their watery domain, typically appearing as green or blue. However, they can also be depicted as white or red, depending on their specific type and nature. While many Klu have human heads, some are shown with multiple serpent heads emerging from their neck or crown. They are sometimes adorned with jewels or precious substances, symbolizing their role as guardians of hidden underground treasures.

The nature of Klu is ambivalent – they can be both benevolent and malevolent. Their disposition largely depends on how they are treated by humans. If their watery domain is disturbed, polluted, or if they are disrespected, Klu can inflict various misfortunes and illnesses. They are particularly known for causing skin diseases (such as leprosy, eczema, and psoriasis), as well as joint problems, swelling, and other water-related ailments. They can also bring about environmental disasters like droughts or floods. Conversely, when honored and treated with respect, Klu can be incredibly beneficial. They are believed to control rain and agricultural fertility, ensuring bountiful harvests. They can also bestow wealth, good health, and long life. Furthermore, they are considered guardians of medicinal plants and numerous precious gems hidden within the earth. Klu are often seen as custodians of vast underground riches, encompassing both material wealth and spiritual knowledge.

The interaction with Klu strongly emphasizes purity and cleanliness, especially concerning water. Polluting water sources—by discarding waste, using harsh chemicals, or even washing dirty clothes in them—is considered a grave offense to the Klu and can lead to immediate retaliation. Offerings of pure substances, such as milk, yogurt, and grains, are made to the Klu to secure their favor. Specific rituals are performed to appease them if their domain has been disturbed or to seek their blessings. The belief in Klu profoundly influences traditional Tibetan environmental ethics, fostering a deep respect for water sources and the natural world, as disturbing them has tangible and often immediate consequences.

The Klu, therefore, represent the vital arteries of the land, controlling the lifeblood of water and safeguarding the secrets of the earth's bounty. Their presence is a constant reminder of the delicate balance required to coexist harmoniously with nature.

THEURANG

The Theurang (ཐེའུ་རང, pronounced "theu-rang") are a class of mischievous and often malevolent spirits in Tibetan and Himalayan folklore, distinct from the larger, more powerful Tsen and Nyen. They are often described as imp-like or hobgoblin-like creatures that inhabit high mountains and the upper atmosphere.

Unlike the Tsen who are mounted warriors or the Klu who are water-bound, the Theurang are known for their chaotic and unpredictable behavior. They are said to delight in causing mischief and chaos, often inflicting illness upon children or being responsible for minor annoyances like hiding or moving household objects. They are also sometimes associated with a pre-Buddhist myth regarding the lineage of the first Tibetan king, Nyatri Tsenpo, who was said to be descended from a monopedal Theurang creature, giving them a place in the ancient origin stories of the Tibetan people. While a source of petty troubles, they are generally considered to be of a lower order than the more formidable spirits, and their veneration or appeasement is often focused on protecting children and the home.

YULHA

The Yulha (ཡུལ་ལྷ, pronounced "yul-lha") is a prominent category of indigenous Tibetan spirits, whose name literally translates to "country god" or "territorial deity." These are protective spirits deeply associated with a specific local area, such as a mountain, a valley, a particular village, or even a specific clan.

Unlike the Tsen, Nyen, or Klu, which are classes of spirits with particular characteristics and domains, a Yulha is a guardian of a specific place. They are often considered the most important deities of a given locale. The most famous Yulha are the gods of Tibet's sacred mountains, such as Mount Kailash. The Yulha is seen as a benevolent protector of the land and its people, ensuring fertility, prosperity, and protection from misfortune. In return, the local community provides offerings and performs rituals to honor them. While a Tsen can be a type of Yulha, the term itself is broader, signifying the fundamental role of a guardian deity tied directly to a specific piece of land and the community that lives upon it.

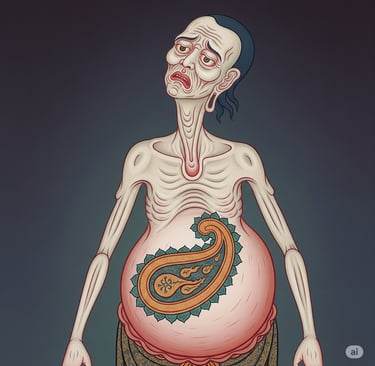

YIDAG

In Tibetan Buddhism, a Yidag (yi-dvags), which translates from Sanskrit as preta, is a being from the "hungry ghost" realm, one of the six realms of existence in Buddhist cosmology. This realm is a powerful representation of the suffering that arises from certain negative actions. A Yidag's existence is defined by an insatiable hunger and thirst, which is a direct consequence of past lives marked by greed, meanness, and miserliness. The classic image of a Yidag is a being with a bloated stomach, symbolizing their immense and constant cravings, and a pinhole-sized throat, which makes it impossible to consume enough food or water to ever feel satisfied. Anything they do manage to find to eat or drink often turns to ash or fire in their mouths, or simply disappears like a mirage before they can consume it. This physical form is a metaphor for the psychological state of a person consumed by constant, unfulfilled desire. The Tibetan term for this emotional state, ser na, also means "meanness" or "lack of generosity," illustrating how the spiritual concept directly relates to a certain type of human behavior. While the suffering of a Yidag is intense, it is not eternal, as all beings in the cycle of rebirth (samsara) can eventually die and be reborn into another realm, based on their karma. This belief serves as a stark reminder of the consequences of selfish actions and a teaching on the importance of generosity and contentment.

SADAG

The Sadag (ས་བདག, pronounced "sah-dahk") are a class of indigenous Tibetan spirits whose name literally translates to "lord of the earth." They are closely related to the Nyen, often being seen as a more specific type of earth spirit. Sadag are the guardians of the land itself, residing in specific patches of soil, rocks, mounds, and local terrain.

The defining characteristic of Sadag is their deep territoriality and their strong connection to the physical ground. Disturbing the earth—through digging, construction, or farming in an unritualized way—is considered a grave offense that can provoke the Sadag's wrath. In retaliation, they are believed to cause various diseases and misfortunes, particularly skin diseases, swelling, and paralysis. As a result, traditional Tibetan culture places a great emphasis on rituals and offerings made to the Sadag before undertaking any activity that involves disturbing the soil, reinforcing a deep, animistic respect for the earth and its unseen inhabitants. The Sadag are a powerful example of the pre-Buddhist spiritual worldview that continues to shape daily life and environmental practices in Tibet.

Mountain Goddess

In Tibetan tradition, the concept of a "mountain goddess" is most famously embodied by Miyolangsangma (མི་གཡོ་གླང་བཟང་མ, pronounced "mee-yo-lang-sang-mah"). She is the goddess who resides on the summit of Mount Everest, known in Tibetan as Chomolungma or "Mother Goddess of the World."

Miyolangsangma is not merely a territorial spirit but a highly revered figure, one of the Five Long-Life Sisters (tshe-ring mched-lnga), a group of deities who were subjugated by the Buddhist master Padmasambhava and sworn to be protectors of the Buddhist Dharma. As a mountain goddess, she is the embodiment of the mountain itself and its surrounding region, and her domain is a source of blessings. She is considered a goddess of inexhaustible giving, bestowing the "jewels of wishes" upon those who are worthy. For this reason, climbers and pilgrims often make offerings and perform rituals at the base of Everest to seek her favor and protection before ascending.

DRE

The Dre (འདྲེ, pronounced "dreh") are a class of malevolent spirits in Tibetan tradition, often translated simply as "ghosts" or "demons." Unlike the territorial spirits like the Tsen or Nyen, a Dre is typically the spirit of a deceased person who died a violent, tragic, or unfulfilled death. Because they are not at peace, they remain tied to the human world, seeking to cause harm.

Dre are considered insidious and dangerous, as they are believed to be able to possess living individuals, causing illness, madness, or mental distress. They are often blamed for strange noises, bad luck, or sudden, inexplicable tragedies within a household. Due to their nature as unhappy, disembodied beings, they are a source of great fear in traditional folklore. Dealing with a Dre often requires specific rituals of exorcism or protective rites performed by a lama or ritual specialist to either pacify the spirit or banish it from the human realm.

Connect

Stay updated with our latest news and events.

turnyourhead@proton.me

E-mail to:

© 2025. All rights reserved.